Why Tymee should be acknowledged as a Korean rap legend

If you’re a K-music fan who also keeps up with Western artists, you’re probably seeing many female rappers’ names in the music charts and awards, especially in the U.S. right now where Cardi B, Megan Thee Stallion, and Doja Cat are dominating. And you might also be thinking of many other female rappers who deserve more love, just as these amazing ones that are having their big moments right now.

In the case of South Korea, it’s not that female-fronted rap is at all unpopular — with shows like Unpretty Rapstar (2015-2016) and Good Girl (2020) we’ve been seeing female rappers getting more attention. Yet, some of these women’s stories remain unknown, or not acknowledged enough. One of these stories is Tymee’s, formerly known as E.Via, the Korean rapper and songwriter born Lee Okju.

Though newer Korean music fans might not be familiar with Tymee’s work, she has been releasing songs for 18 years, with recent years seeing less and less music from her. Some may know Tymee for the beefs she has been involved in throughout her career, such as the one with Jolly V before and during Unpretty Rapstar, or her super brief participation on Show Me The Money. Or maybe you’ll remember her as E.Via, the controversial rapper who released meme-worthy songs such as “Oppa! Can I Do It?” before memes were even a thing.

But Tymee is so much more than the dramas and the eccentric songs — she’s barely acknowledged by what they represented for the music scene in Korea. Here are eight reasons why she was a pioneer, a total legend, and why she should be acknowledged as such.

She Pretty Much Pioneered Aegyo-Rap

Lee Okju started her career as an underground rapper that went by the name of Napper. When she debuted in the Korean pop industry formally as the controversial E.Via, her impeccable flow and impressive breath control were still there — but the deep voice she used to rap with previously gave place to a cute, high pitched, almost unrecognizable timbre.

Along with her clothes and overall shy girl attitude, the baby voice was not exactly what one would expect from a serious rapper, and the aegyo merged with fire rap. E.Via’s songs would also be the first time Tymee would present her fast rap, a side of hers that would also become her signature – which was a peculiar combination too.

But, whether you’d find her laughable or good, you can’t deny that E.Via was somewhat fascinating to listen to, and years later, the aegyo rap she became famous for would infiltrate the K-pop industry, becoming basically a mandatory in K-pop songs by girl groups such as Girls Generation’s “I Got a Boy.”

Also on KultScene: BIG NAUGHTY TALKS ‘BUCKET LIST’ & BEING A KOREAN RAP PRODIGY

Her Music Was Once Banned In Korea

In spite of looking and sounding innocent, E.Via’s songs weren’t really all that suitable for kids. “Oppa! Can I do it?,” the lead single from her debut album, was pretty ambiguous. It wasn’t really clear what she was asking her oppa permission for: the album version included her moaning, while the lyrics also hint at E.Via asking him to hear her rap. The provocative content and slang led music shows such as Music Bank to ban her performances. E.Via, who wrote the lyrics of “Oppa! Can I do it?”, never fully addressed what the song was intended to be — but such suggestiveness would become a part of her brand.

As much as it may be disturbing to hear an infantilized woman performing sexually suggestive songs, or to hear a woman asking a guy permission to do anything at all, the song raised discussions about what artists and women can do, and the ban would only raise the public’s attention and interest to E.Via and her upcoming music.

She Featured Herself On A Song

So far, you’ve learned that Tymee went by different names during her career. Each one of these “personas” had their own features, but they’re all pretty much different sides of her, representing different stages of her life. But could these personas meet each other?

Alter egos are quite common in rap, but there are very few cases of rappers featuring “themselves” in a song — and the most popular ones we can think of, like Logic feat. Young Sinatra’s “Warm It Up,” weren’t released before E.Via’s “My Medicine,” a song in which E.Via featured no one less than Napper, her old alias.

In this sweet yet sad song, Napper raps and E.Via sings. It’s not only an example of Lee Okju’s versatility and emotional depth – you can just feel the pain in her voice, even if you don’t understand the lyrics – but also her creativity. Who would think of such a collab? It’s just genius to bring your two personas to meet and perform with each other.

She Broke Free & Prioritized Her Artistic Freedom

E.Via brought Lee Okju fame and success, but she wasn’t happy, and was also severely mistreated and not properly paid by her talent agency, DLine Art. She couldn’t put up with it further than early 2013, when she announced that she was leaving the company.

But breaking free from her contract wasn’t easy: she had to go to court, and ended up with little to no rights to her music, and not allowed to use the name E.Via. She then changed her stage name to Tymee, and later signed to rapper Outsider’s ASSA Communication, where she would find more creative freedom and control. On the songs she released thereafter, such as “On The River,” she spoke about her mental health issues and how she almost gave up on music. The name “Tymee” would symbolize her desire to be “tied” to music, as a promise that she wouldn’t let anything or anyone steal her passion for it.

Was An IP Genius During Diss War

In 2013, when U.S. rapper Big Sean released “Control,” a featured verse by Kendrick Lamar would inspire the beginning of a diss war in the Korean hip-hop scene. Initiated by rapper Swings (with whom Tymee had history), the war consisted of many rappers shooting and firing back at each other by writing their own verses over the “Control” beat. The diss war had pretty much only male rappers doing it, until Tymee stepped in.

Recently signed off from her previous label and recovering from what almost ended her career forever, she definitely had a lot to say, and she didn’t hold back. “Cont Lol,” which is a play on the words “Control” and “Laughing out loud,” referenced how she found the other rappers’s skills comically laughable. There was also a reference to the video game series League of Legends, showing Tymee’s angry views on hip-hop culture, stating her place as woman in a male-dominated industry (“I’m not a king, but I’m a queen”), dissing rappers and everyone who mistreated her in the past, with no mercy or filters. And as if that weren’t enough, “Cont Lol” also brought back E.Via, — sort of. In a maneuver that would make Intellectual Property lawyers tremble, Tymee channelled her former persona without the need to say her name or to mention anything about her previous works or label, just by using the cute voice she was famous for.

She Was The Best Unpretty Rapstar Contestant To Not Make It To The Finals

After a short passage in Show Me The Money, during which she got eliminated for forgetting her lyrics, Tymee was given another chance to compete in a rap survival TV show, this time, one meant for female rappers only. Tymee’s participation in the first season of Unpretty Rapstar again got attention for her beef with Jolly V, a rapper who dissed her in the past, to which she responded. They both also competed in the same season of Show Me The Money. While Tymee didn’t make it into the semifinals and isn’t even featured on the TV show’s official soundtrack, her performances there were some of the best of her entire career. She shone in a battle against Jace, and later in a collaboration with the same artist. These two verses were so impactful that Tymee would incorporate them into later elements of her career, performing the first one at live concerts and using the second in “Octagon,” a collaboration with Outsider and other label mates.

When you hear Tymee’s crystal clear pronunciation in these verses, her incredible rhyme schemes, lyricism, fierce delivery, and flow, it’s hard to understand why she isn’t considered Yoon Mirae-level of reference for women in South Korea’s hip-hop scene, or why her skills aren’t given the same glory as Korean hip-hop icon Verbal Jint’s.

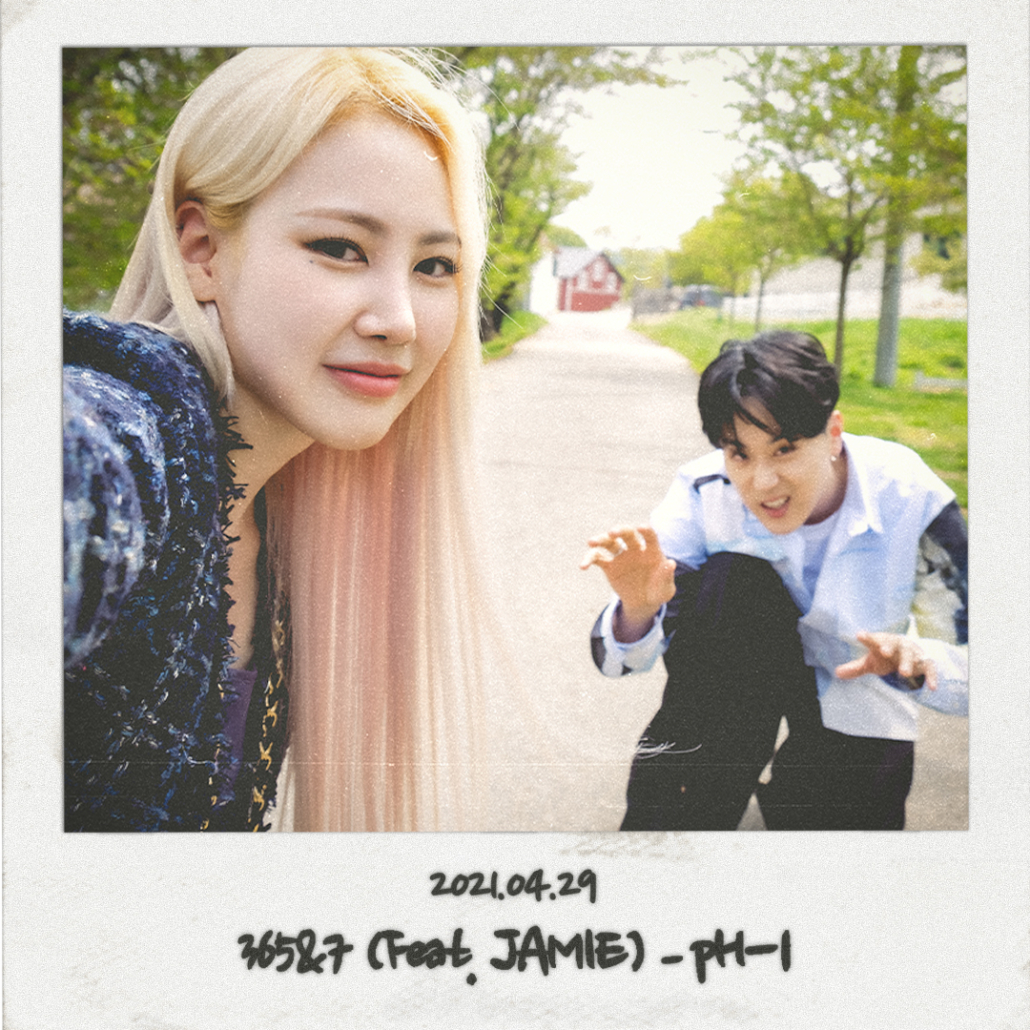

Also on KultScene: PH-1 TALKS CREATIVE PROCESS, THE FUTURE, & LATEST SINGLE ‘365&7’ [INTERVIEW]

One Of The First Artists In Korea To Use The Word “Feminist” In A Song

Tymee’s history with Unpretty Rapstar wouldn’t end after she got eliminated from Season 1. In 2016, she would be invited to be a guest judge in the third season, and also released a diss song to the show on her Youtube channel. On “Fuck Pretty Rapstar,” she criticized the contestants who care more about their looks than their rap skills, and proclaimed herself as a feminist that wants to see a fair race in the show regardless of its gender scope.

There isn’t much, if any, history of feminism being mentioned in mainstream Korean songs before “Fuck Pretty Rapstar.” Feminism, as a term, wasn’t that widely known there in 2016 (when participating in a livestream, Tymee was even asked what that word meant). And to be fair, until very recently, it still wasn’t that well known or perceived, as we’ve seen from the controversies that follow female K-pop stars’ when they’re perceived being feminist.

Makes The Music She Wants

Nowadays, Tymee is a part of a music crew called Freezy Bone and isn’t under any label. She is an independent artist whose latest music is less hard rap-driven and leans more towards smoother alternative hip-hop, although her great lyricism is still present. She has said many times she’s not ashamed of her past, but as is noticeable from the abrupt change of style, she doesn’t let it define what she’s going to do either.

With almost a 20-year career, having gone through underground and Korea’s mainstream, and several ups and downs, Tymee’s story is one of determination and overcoming adversity with her best weapon: talent. It’s also a story about identity. Tymee has been through many different phases, styles, and names, but her talent would always show through — even when she wasn’t being 100% true to herself, she still excelled as a rapper— and her love for music would always win. Regardless of what she’ll do in the future or what kind of music she’ll release, Lee Okju should be acknowledged for just how good she is, and for all the fields and forces she touched or impacted.

Don’t forget to subscribe to the site and follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Tumblr to keep up with all of our articles.

KultScene is a writer-driven website dedicated to creating a platform where diverse voices’ takes on K-pop can be heard. If you like this post and would like to see more, please consider contributing to KultScene’s writers fund. KultScene’s writers are compensated for their work, time, and insight. Email us for more details.